You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Japanese history’ tag.

Overview of Japanese History up through the Classical (Heian) Period

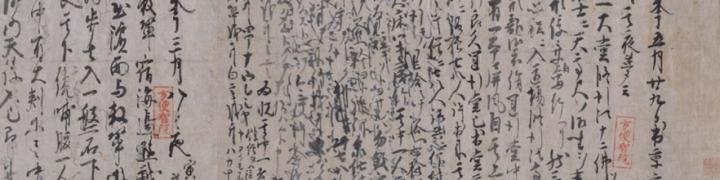

Japan does not appear in history until 57 AD when it is first mentioned in Chinese histories, where it is referred to as “Wa.” The Chinese historians tell us of a land divided into a hundred or so separate tribal communities without writing or political cohesion. The Japanese do not start writing their histories until around 600 AD; this historical writing culminates in 700 AD in the massive chronicles, The Record of Ancient Matters and the Chronicles of Japan. These chronicles tell a much different and much more legendary history of Japan, deriving the people of Japan from the gods themselves.

The Japanese are late-comers in Asian history. Preceding their unification and their concern with their own history in the latter half of the first millenium AD is a long period of migration and settlement. Where did the Japanese come from? Why did they settle the islands? What did life look like before history was written down?

In order to get a handle on ancient Japanese history, it helps to consider that it is driven by outside influences. The first involved the settlement of Japan by a group of peoples from the Korean peninsula in the third century BC. Overnight they transformed the stone-age culture of Japan into an agricultural and metal-working culture. These early immigrants are ultimately the origin of Japanese language and culture.

The second great push in Japanese history was contact with China from 200 AD onwards. From the Chinese, who demanded that Japan be a tribute state to China, the Japanese adopted forms of government, Buddhism, and writing. While Japanese culture ultimately derives from the immigrants of the third century BC, the bulk of Japanese culture is forged from Chinese materials—a fact that will drive an entire cultural revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as scholars attempt to reclaim original Japanese culture from its Chinese accretions.

The overwhelming fact that suffuses every aspect of Japanese culture is its geography. Japan is a series of islands—the group consists of over 3000 islands of which 600 are inhabited. The four main islands, Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido dominate Japanese history, however. The largest island is Honshu, but the overall geographical area of the inhabited islands is less than California. The climate is pleasantly moderate, for the islands lie in the path of the Black Current which flows north from the tropics. All the islands are mountainous and subject to a variety of natural disasters, especially earthquakes and tsunamis. The mountainous terrain leaves its mark on Japanese culture; since the mountains provide natural and difficult barriers, political life in Japan centered around regional rather than national governments. The earliest flowering of Japanese history took place in the low-lying plains on the island of Honshu, especially the Yamato plain in the south—a region that gave its name to the first “official” name for Japan, Yamato. There the very first Japanese kingdom arose and provided the basis of future Japanese civilizations.

Japan as a series of islands has always been isolated from the mainland from about 10,000 B.C. to the present day. For this reason, the original inhabitants managed to hold on to stone-age life long after the regions to the west had urbanized. This island status has also protected Japan from foreign invasions. Only twice in Japanese history has the island been successfully overrun by foreigners: in the third century BC by the wave of immigrations from the Korean peninsula, and in 1945 by the United States.

The areas of Japan which have shown the most cultural change are those, as you might imagine, that are closest to the mainland of Asia. The southern island of Kyushu and the southwestern peninsula of Honshu lie close to the Korean peninsula. It is in this region that the Japanese first immigrated into Japan in the third century BC, and it is in this region that the first state in Japan was established: the Yamato State on the Yamato peninsula (the southwesternmost peninsula on Honshu).

Despite the late arrival of Japan into written history, the beginnings go back ten thousand years to a mysterious people which would eventually produce a unique and vital culture, the Jomon.

Prehistoric Japan:

Although the Japanese do not settle Japan until the third century B.C., humans had lived in Japan from about 30,000 B.C.. For Japan was not always an island. During the Ice Ages, it was connected to the Korean peninsula by means of a land bridge. All four main Japanese islands were connected, and the southern island of Kyushu was connected to the Korean peninsula while the northern island of Hokkaido was connected to Siberia. Stone Age humans crossed this land bridge in much the same way they crossed the Bering land bridge into the Americas. We can date these humans back to around 30,000 B.C. from the flint tools that they left behind.

The Jomon:

Then around 10,000 B.C., these original inhabitants developed a unique culture which lasted for several thousand years: the Jomon culture. As with all preliterate people, all we know of them comes from fragments of artifacts and the imaginative guessing of anthropologists and archaeologists. Jomon means “cord pattern,” for these people designed cord patterns on their pottery—the oldest of its kind in human history. Pottery, however, is a characteristic of Neolithic peoples; the Jomon, however, were Mesolithic peoples (Middle Stone Age). All the evidence shows that they were a hunting, gathering, and fishing society that lived in very small tribal groups. But in addition to making pottery, they also fashioned mysterious figurines that appear to be female. An ancient goddess worship?

We divide the Jomon into six separate eras—ten thousand years, after all, is a long time and even preliterate cultures change dramatically over time. These eras are the Incipient, Initial, Early, Middle, Late, and Final Jomon periods.

The Incipient Jomon, which is dated from about 10,500 B.C. to 8,000 B.C. has left us only pottery fragments. These pottery fragments were made by a people living in the Kanto plain on the eastern side of Honshu, the plain on which Tokyo is located. We have little idea what these fragments looked like when they were actually in one piece, but we believe that they were very small, rounded pots. The Incipient Jomon pots are a major challenge to understanding human cultures, for they represent the very first ceramics in human history, predating Mesopotamian ceramics by over two thousand years. The standard anthropological line on the development of human arts asserts that pottery-making developed after agriculture and is characteristic of a more sedentary culture. The Incipient Jomon, however, were hunter-gatherers who lived in nomadic small groups. Yet they developed the art of pottery long before agriculture was introduced into Japan—in fact, the Incipient Jomon invented pottery-making long before any human was introduced to agriculture. The Incipient Jomon, then, demonstrate that pottery-making is a human technology independent and distinct from agriculture.

The Initial Jomon, which lasted from 8,000 B.C. to 5,000 B.C. is distinguished by the fact that we have pretty complete pots (isn’t archaeology exciting?) that were used to boil food. Like the fragments from the Initial Jomon, these aren’t just plain old pots, but are inticrately decorated in the “cord-like” structure that characterizes Jomon.

The Early Jomon, from 5000 to 2500 B.C., corresponds to the single most interesting couple thousand years in human history. At the end of the last ice age, around 14,500 years ago, the world began to slowly warm. Between 5000 and 2500 B.C., the world reached its warmest in the millenia following the ice age—during this period, the average global temperature was about four to six degrees farenheit higher than it is today. Never again would the world be as warm as it was in these two centuries. Here’s the exciting thing: corresponding the steady warming of the earth was the development of agriculture, the single most important technological invention of human beings. Corresponding the warmest period since the last ice age were tremendous innovations in human habitation. It was in this period that human beings all over the world began to live in a more sedentary manner—at the beginning of this period, human beings begin to live in substantially sized villages; towards the end of this period, the very first human cities appear. The Jomon were no exception to this world-wide phenomenon. Completely cut off from all other humans, the Jomon also began to live in large villages in a settled lifestyle. These villages consisted of large pit-houses; the floors of these houses are about a foot below ground level. It seems they lived in extended family groups. The Jomon also developed their pottery work even further: they began to fashion figurines. It’s not clear what they are, animal or human, but they are the first Japanese sculptural art.

In the Middle Jomon, from 2500-1500 B.C., the Jomon migrated from the Kanto plain into the surrounding mountainside. While the Old Kingdom Egyptians were building pyramids, the Yellow River kings developing the first centralized states in China, and the Sumerians building the very first urban centers, the Jomon, who had no awareness of people off their island, began to live in very large villages and developed very simple agriculture or proto-agriculture. They were no longer hunter-gatherers, but rather a skilled and settled people that developed increasingly sophisticated artwork with magnificent decorations. Their figurines now distinguish between animals and humans, and their human figurines have tantalizing but perplexing gestures whose meaning is now lost to us.

The Late (1500-1000) and Final (1000-300) Jomon corresponded to the neoglaciation stage in modern climactic history. The world cooled noticeably (colder than today), and the Jomon migrated back down to the Kanto plain. At this point, the Jomon developed an identifiable religion—they produce a remarkable number of figurines and stone circles constructed outside the main villages begin to appear. The figurines they produce are largely heavy female figurines which suggests that the Jomon religion was a goddess religion.

The Yayoi:

The Jomon culture, in essence a Mesolithic culture (although they display Neolithic traits, such as pottery-making), thrived in Japan from the eleventh century to the third century B.C., when it was displaced by a wave of immigrants from the mainland. These were the Yayoi, and their origins lay in the north of China. Northern China was originally a temperate and lush place full of forests, streams, and rainfall. It began to dry out, however, a few thousand years before the common era. This dessication, which eventually produced one of the largest deserts in the world, the Gobi, drove the original inhabitants south and east. These peoples pushed into Korea and displaced indigenous populations. Eventually, these new settlers were displaced by a new wave of immigrations from northern China and a large number of them crossed over into the Japanese islands. For this reason, the languages of the area north of China, the language of Korea, and Japanese are all in the same family of languages according to most linguists. Because Mongolian (spoken in the area north of China) is also part of this language family and because the Mongolians conquered the world far to the west, this means that the language family to which Japanese belongs is spoken across a geographical region from Japan to Europe. The westernmost language in this family is Magyar, spoken in Hungary, and the easternmost language in this family is Japanese.

The Yayoi brought with them agriculture, the working of bronze and iron, and a new religion which would eventually develop into Shinto (which wasn’t given this name until much, much later). While we don’t know what these immigrations did to the indigenous peoples, there are several possibilities. According to one theory, which is widely accepted in Japan, the waves of Yayoi immigrants were very small. While they brought new technologies with them, they were nevertheless assimilated into the native Jomon culture. By this account, Japanese culture, particularly as it is represented by the Shinto religion, is very ancient and indigenous Japan. Some Japanese believe that the Jomon spoke an Austronesian language, that is, that the Jomon were more closely related to south Pacific islanders and that Japanese is still largely a Pacific island language. In the West, historians believe that the Yayoi displaced the indigenous Jomon and thus ended their culture permanently. The Yayoi displaced the indigenous language, social patterns, and religion of the original inhabitants. In this view, Japanese culture is a foreign import deriving ultimately from the north of China and ancient Korea, a view that is not popular among the modern Japanese.

Whatever the origins of Japanese culture, it is clear that the Japanese language, social structure, and religion can be dated no farther back in Japan than the Yayoi immigrants. So for all practical purposes, the Yayoi are a new beginning in Japanese culture. The transition was dramatic, far surpassing even the transition represented by the industrial revolution. Japanese culture changed overnight with these new immigrants; eight thousand years of cultural placidity was dramatically hoisted into the agricultural age.

The Yayoi lived in clans called uji . The clans were headed by a single patriarchal figure who served as both a war-chief and as a priest. Each clan was associated with a single god which the head of the clan was responsible for; all the ceremonies associated with that god were headed or performed by the head of the clan. These gods, called kami , represented forces of nature or any other wondrous aspect of the world; the Yayoi, we believe, also had accounts of the creation of the world by gods. When one uji conquered another, it absorbed its god into its own religious practices. In this way, the Yayoi slowly developed a complex pantheon of kami that represented in their hierarchy the hierarchy of the uji .

The Yayoi lived primitively. They had no system of writing or money; they dressed largely in clothes made from hemp or bark. Marriages were frequently polygamous, but women held a fairly prominent place in the society of the uji . It is probable that women even served as clan-heads or priests; support for this possibility comes from the Chinese histories that first discuss the Japanese.

The relationships between the uji were complex; slowly, territorial conflict gradually produced what came close to small states. The first Japanese state, however, would be built on the Yamato peninsula, the area into which Chinese influence began to flow in 200 AD.

The Yamato State:

The Yamato peninsula, on the southwesternmost portion of the island of Honshu, has historically been the region through which cultural influence from the mainland has passed into Japan. Beginning in 300 A.D., a new culture distinguished itself from Yayoi culture in the area around Nara and Osaka in the south of Honshu. This culture built giant tomb mounds, called kofun , many of which still exist; these tomb mounds were patterned after a similar practice in Korea. It is from these tomb mounds that these people derive their name: the Kofun. For two hundred years, these tombs were filled with objects that normally filled Yayoi tombs, such as mirrors and jewels. But beginning in 500 A.D., these tombs were filled with armor and weapons. So we know that around this time, a new wave of cultural influence had passed over from Korea into Japan.

Yamato Japan

The earliest Japanese state we know of was ruled over by Yamato “great kings”; the Yamato state, which the Japanese chronicles date to 500 A.D., that is, the time when a new wave of Korean cultural influence passed through southern Japan, was really a loose hegemony. Yamato is the plain around Osaka; it is the richest agricultural region in Japan. The Yamato kings located their capital at Naniwa (modern day Osaka) and enjoyed a hegemony over the surrounding aristocracies that made them powerful and wealthy. They built for themselves magnificent tomb-mounds; like all monumental architecture, these tombs represented the wealth and power of the Yamato king. The keyhole-shaped tomb-mound of Nintoku is longer than five football fields and has twice the volume of the Great Pyramid of Cheops.

According to the Japanese chronicles, the court of the Yamato kings was based on Korean models for the titles given to the court and regional aristocrats were drawn from Korean titles. As in Yayoi Japan, the basic social unit was the uji ; what had been added was an aristocracy based on military readiness. This military aristocracy would remain the single most powerful group in Japanese history until the Meiji restoration in 1868. The various aristocratic families did not live peacefully together; the Yamato court witnessed constant struggles among the aristocratic families for power.

During this period, Japan had a presence on the Korean peninsula itself. Korea was in its most dynamic cultural and political period; the peninsula itself was divided into three great kingdoms: Koguryo in the north, Paekche in the east, and Silla in the west. Paekche understood the strategic importance of Japan and so entered into alliance with the Yamato state. This connection between the Yamato court and Paekche is culturally one of the most important events of early Japanese history. For the Paekche court sent to Japan Korean craftspeople: potters, metal workers, artists, and so on. But they also imported Chinese culture. In the fifth or sixth century, the Koreans imported Chinese writing in order to record Japanese names. In 513, the Paekche court sent a Confucian scholar to the Yamato court. In 552, the Paekche sent an image of Buddha, some Buddhist scriptures, and a Buddhist representative. These three imports—writing, Confucianism, and Buddhism—would transform Japanese culture as profoundly as the Yayoi immigrations had done.

Prince Shotoku

****************************

APPENDIX READING: “The great cultural hero of early Japanese history was the Imperial Prince Mumayado no Toyotomimi who, with the ruling name Shotoku, became regent under his mother, Empress Suiko. His greatest legacy to Japanese history was the Seventeen Article Constitution which spelled out the philosophic and religious principles on which Japanese Imperial government would be based. In line with his foundational role in Japanese political identity, his birth, like that of Buddha, is a miraculous birth: born without pain, he speaks as an adult from the moment of his birth.

What follows is a short account of Shotoku’s birth and a brief description of his upbringing from the Nihongi. The text stresses his education first in Buddhism (the Inner Doctrine) and then in Confucianism and the Confucian classics (the Outer Classics). The general narrative of the Nihongi outlines two developments: the evolution of Japanese government in Confucian principles and the gradual adoption of Buddhism among the Japanese. The culmination of this development, according to the argument in the Nihongi, is Shotoku and his Seventeen Article Constitution.

Summer, 4th month, 10th day.

The Imperial Prince Mumayado no Toyotomimi was appointed Prince Imperial. He had general control of the Government, and was entrusted with all the details of administration. He was the second child of the Emperor Tachibana no Toyo-hi. The Empress-consort his mother’s name was the Imperial Princess Anahobe no Hashibito. The Empress-consort, on the day of the dissolution of her pregnancy, went round the forbidden precinct, inspecting the different offices. When she came to the Horse Department, and had just reached the door of the stables, she was suddenly delivered of him without effort.1 He was able to speak as soon as he was born, and was so wise when he grew up that he could attend to the suits of ten men at once and decide them all without error. He knew beforehand what was going to happen. Moreover he learnt the Inner Doctrine2 from a Koryo Priest named Hye-cha, and studied the Outer Classics3 with a doctor called Hak-ka. In both of these branches of study he became thoroughly proficient. The Emperor his father loved him, and made him occupy the Upper Hall South of the Palace. Therefore he was styled the Senior Prince Kamu-tsu miya4, Aluma-ya-do Toyotomimi.”

Translated by W.G. Aston, Nihongi (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1896), 278-279

Introduction and edited by Richard Hooker

**************************************************

The most important period in early Japan occurs during the reign of Empress Suiko, who ruled from 592 to 628 A.D.. In the latter years of the 500’s, the alliance between Paekche and the Yamato state broke down; this eventually led to the loss of Japanese holdings on the Korean peninsula. Waves of Koreans migrated to Japan, and, to make matters worse, the powerful military aristocracies of the Yamato state began to resist the Yamato hegemony.

The Yamato court responded to these problems by adopting a Chinese-style government. In the early years of the seventh century, they sent envoys to China in order to study Chinese government, society, and philosophy. At home, they reorganized the court along the Chinese model, sponsored Buddhism, and adopted the Chinese calendar. All of these changes were adminstered by Prince Shotoku (in Japanese, Shotoku Taishi, 573-621) who was the regent of the Yamato court during the reign of Empress Suiko. His most important contribution, however, was the writing and adoption of a Chinese-style constitution in 604 A.D.. The Seventeen Article Constitution (in Japanese, Kenpo Jushichijo) was the earliest piece of Japanese writing and formed the overall philosophic basis of Japanese government through much of Japanese history. This constitution is firmly based on Confucian principles (although it has a number of Buddhist elements). It states the Confucian belief that the universe is composed of three realms, Heaven, Man, and Earth, and that the Emperor is placed in authority by the will of Heaven in order to guarantee the welfare of his subjects. The “great king” of earlier Japanese history would be replaced by the Tenno, or “Heavenly Emperor.” The Seventeen Article Constitution stressed the Confucian virtues of harmony, regularity, and the importance of the moral development of government officials.

Shotoku, however, was also a devout Buddhist. The second article of the constitution specifically enjoins the ruler to value the Three Treasures of Buddhism. The overall Constitution, however, is overwhelmingly Confucian.

Taika Reform Edicts:

The constitution was followed by a coup against the ruling Soga clan, from which Shotoku was derived. The new emperor, Kotoku Tenno (645-655), began an energetic reform movement that culminated in the Taika Reform Edicts in 645 A.D.. These edicts were written and sponsored by Confucian scholars in the Yamato court and essentially founded the Japanese imperial system. The ruler was no longer a clan leader, but Emperor that ruled by the Decree of Heaven and exercised absolute authority. Japan would no longer be a set of separate states, but provinces of the Emperor to be ruled by a centralized bureaucracy. The Reform Edicts demanded that all government officials undergo stringent reform and demonstrate some level of moral and bureaucratic competency. Japan, however, was still largely a Neolithic culture; it would take centuries for the ideal of the Chinese style emperor to take root.

Shinto:

Because of the thought and philosophy of the Tokugawa period in Japan (1600-1868), nothing says “Japan” like the Shinto religion. The Tokugawa “Enlightenment” inspired a group of thinkers who studied what they called kokugaku , which can be roughly translated “nativism,” “Japanese Studies,” or “Native Studies.” Kokugaku was no dry-as-dust academic discipline as the term “Japanese Studies” seems to imply; it was a concerted philosophical, literary and academic effort to recover the essential “Japanese character” as it existed before the early influences of foreigners, especially the Chinese, “corrupted” Japanese culture. Recovering the essential Japanese character meant in the end distinguishing what was Japanese from what is not and purging from the Japanese culture various foreign influences including Confucianism (Chinese), Taoism (Chinese), Buddhism (Indian and Chinese), and Christianity (Western European). The kokugakushu (“nativists”) focussed most of their efforts on recovering the Shinto religion, the native Japanese religion, from fragmentary texts and isolated and unrelated popular religious practices.

Despite this optimism, Shinto is probably not a native religion of Japan (since the Japanese were not the original “natives” of Japan), and seems to be an agglomeration of a multitude of diverse and unrelated religions and mythologies. There really is no one thing that can be called “Shinto,” since there are a multitude of religious cults that gather beneath this category. The name itself is a bit misleading, for “Shinto” is a combination of two Chinese words meaning “the way of the gods” (shen : “spiritual power, divinity”; tao : “the way or path”) and was first used at the beginning of the early modern period. The Japanese word is kannagara: “the way of the kami .” Calling the religion of the early Japanese “Shinto” is a gross and unsupportable anachronism.

Despite the difficulty in pinning down the form and nature of early Shinto, several general assertions can be drawn about it. First, early Shinto was a tribal religion, not a state one. Individual tribes or clans, which originally crossed over to Japan from Korea, generally held onto their Shinto beliefs even after they were organized into coherent and centralized states.

Second, all Shinto cults believe in kami , which generally refers to the “divine.” Individual clans (uji ), which were simultaneously political, military, and religious units, worshipped a single kami in particular which was regarded as the founder or principal ancestor of the clan. As a clan spread out, it took its worship of a particular kami with it; should a clan conquer another clan, the defeated clan was subsumed into the worship of the victorious clan’s kami . What the kami consists of is hard to pin down. Kami first of all refers to the gods of heaven, earth, and the underworld, of whom the most important are creator gods—all Shinto cults, even the earliest, seem to have had an extremely developed creation mythology. But kami also are all those things that have divinity in them to some degree: the ghosts of ancestors, living human beings, particular regions or villages, animals, plants, landscape—in fact, most of creation, anything that might be considered wondrous, magnificent, or affecting human life. This meant that the early Japanese felt themselves to be under the control not only of the clan’s principal kami , but by an innumerable crowd of ancestors, spiritual beings, and divine natural forces. As an example of the potential for divinity: there is a story of an emperor who, while travelling in a rainstorm encountered a cat on a porch that waved a greeting to him. Intrigued by this extraordinary phenomenon, the emperor dismounted and approached the porch. As soon as he reached the porch, a bolt of lightning crashed down on the spot his horse was standing and killed it instantly. From that point on, cats were, in Shinto, worshipped as beneficent and protective kami ; if you walk into a Japanese restaurant, you are sure to find a porcelain statue of the waving cat which protects the establishment from harm.

Third, all Shinto involves some sort of shrine worship, the most important was the Izumo Shrine on the coast of the Japan Sea. Originally, these shrines were either a piece of unpolluted land surrounded by trees (himorogi ) or a piece of unpolluted ground surrounded by stones (iwasaka ). Shinto shrines are usually a single room (or miniature room), raised from the ground, with objects placed inside. One worshipped the kami inside the shrine. Outside the shrine was placed a wash-basin, called a torii , where one cleaned one’s hands and sometimes one’s face before entering the shrine. This procedure of washing, called the misogi , is one of the principal rituals of Shinto, which also included prayer and spells. One worships a Shinto shrine by “attending” it, that is, devoting oneself to the object worshipped, and by giving offerings to it: anything from vegetables to great riches. Shinto prayer (Norito ) is based on koto-dama , the belief that spoken words have a spiritual power; if spoken correctly, the Norito would bring about favorable results.

Unfortunately, we know almost nothing at all about early Shinto, since nobody wrote about it. Early Shinto may, in fact, be a myth; what is called early Shinto may simply be a large number of unrelated local religions that began to combine with the advent of centralized states. History has accreted an enormous amount of non-Shinto ideas into this original religion: Buddhism, Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism have all significantly changed the religion.

The two great texts of Shinto belief and mythology, the Kojiki (The Records of Ancient Matters ) and the Nihongi (Chronicles of Japan ), were written down around 700 A.D., two centuries after Buddhism had been declared the state religion of Japan. Although these texts contain the only versions of Shinto mythology, including Shinto creation stories, both of these texts are heavily influenced by both Buddhism and Confucianism and the stories of the kami had been deeply corrupted by Chinese and Korean thought long before.

The Nara Period:

The most profound change in Japanese government was the adoption of Chinese, particularly Confucian, models of government in Prince Shotoku’s Seventeen Article Constitution . The reforms undertaken by Shotoku not only addressed the internal problems the Yamato court was faced with, they also dramatically changed Japanese history.

The various Japanese states are named for the regions in which the capital was located. In 710, the capital was moved north to Nara. It was a carefully planned city laid out on a rigorous grid after the Chinese capital of Chang-an. Meant to be a permanent capital, it was moved again only eighty years later.

Japan during the Nara period, however, was primarily an agricultural and village-based society. Most Japanese lived in pit houses and worshipped the kami of natural forces and ancestors. Building a capital city on the model of a Chinese capital produced a dramatic alienation of Japanese aristocracy from the Japanese population. In this region of villages, pit-houses, and kami -worship, grew up a city of palaces, silks, wealth, Chinese writing and Chinese thought, and Buddhism. The Nara capital represents the definitive break of the Japanese aristocracy from their roots in the uji .

The most influential cultural development in the Nara was the flowering of Buddhism. Several schools of Buddhist thought imported from T’ang China made their way to the capital city. For the most part, Buddhism was a phenomenon of the capital city well into the Heian period. However, the vitality of Buddhism at this time led to a closer integration of Buddhism with Japanese government. The Nara emperors in particular deeply reverenced a Buddhist teaching called the Sutra of Golden Light ; in it, Buddha is established not only as a historical human being but also as the Law or Truth of the universe. Each human has reason, prajna , with which to distinguish good from bad. The life of reason, then, is the beginning of a proper Buddhist life. Politically, the sutra claimed that all human law must reflect the Ultimate Law of the universe; however, since law was a phenomenon of the material world, it was subject to change. This gave Japanese monarchs a moral basis for their rule and a justification for adapting rules and laws to changing circumstances.

The devoutness that the Nara emperors held for Buddhism guaranteed its rapid and dramatic expansion into Japanese culture. Although Buddhism entered Japan in 518, it was during the Nara period that it became a solid presence in Japanese culture.

The Heian period

The Heian period (794-1192) was one of those amazing periods in Japanese history, equaled only by the later Tokugawa period in pre-modern Japan, in which an unprecedented peace and security passed over the land under the powerful rule of the Heian dynasty. Japanese culture during the Heian flourished as it never had before; such a cultural efflorescence would only occur again during the long Tokugawa peace. For this reason, Heian Japan along with Nara Japan (710-794) is called “Classical” Japan.

The Nara period was marked by struggles over the throne and which of the clans would control that throne. In order to quiet these disturbances, the capital was moved in 795 to modern-day Kyoto, which at that time was give the name “Heian-kyo,” or city of peace and tranquility. The struggles for the throne ceased, but Japan still did not completely unite under a central government. What happened instead was that power accumulated under a single family, the Fujiwara, who managed to skillfully manipulate and hold onto their power in the face of changes and rivalry for over three centuries. With such stability, the Heian imperial court at thrived.

The Japanese at the Heian court began to develop a culture independent of the Chinese culture that had formed the cultural life of imperial Japan up until that point. First, they began to develop their own system of writing, since Chinese writing was adopted to an entirely different language and world view. Second, they developed a court culture with values and concepts uniquely Japanese rather than derived from imperial China, values such as miyabi, “courtliness,” makoto , or “simplicity,” and aware, or “sensitivity, sorrow.” This culture was forged largely among the women’s communities at court and reached their pinnacle in the book considered to be the greatest classic of Japanese literature, the Genji monogatari (Tales of the Genji) by Lady Murasaki Shikibu.

Heian government solidified the reforms of the late Yamoto and Nara periods. At the top of the official hierarchy was the Tenno, or “Divine Emperor.” The Emperor was both Confucian and Shinto; he ruled by virtue of the Mandate of Heaven and by legitimate descent from the Shinto Sun Goddess, Amaterasu. Because of this, the imperial line of descent has remained unbroken in Japanese history from the late Yamato period.

The government hierarchy beneath the Emperor was built along Chinese lines. The Japanese borrowed the T’ang Council of the State, which held most of the power in Japan. The most powerful clans vied for the position as Council of State, for from that seat they could control the emperor and the entire government itself. Like T’ang government, there were several ministries (eight instead of six). There was, however, a profound difference between T’ang China and Heian Japan. China was a country of some sixty-five million people; Japan was a loose confederacy of some five million people. The Chinese lived relatively prosperously, and T’ang China had by and large become an urban and an industrial culture. Japan, on the other hand, was still very backward when one left the capital city of Heian-kyo. Uji bonds were still felt, and outlying areas still exercised a degree of autonomy. The result for court government was very simple: most of court government concerned the court alone. There were six thousand employees of the imperial government; four thousand administered the imperial house. So the Heian court was not overly involved in the day to day governing of outlying provinces, which numbered sixty-six.

In both the Nara period and the Heian period, regional chiefs were replaced by court-appointed governors of the provinces. This was a demotion for the traditional aristocracy; it did not mean, however, that Heian government exercised a great deal of control over these regional governors who ran their provinces more or less autonomously.

The Heian period, though, was one of remarkable stability. There was little dissension or disagreement in the government itself or between the government and provincial governors. The only problems were conflicts between uji either vying for territory or for influence at the court.

In the earliest periods in Japan, warfare was largely confined to battles between separate uji , or clans. The clans would go into battle under a war-chief; there was no separate class of soldiers. At the emergence of the Yamato state, new techniques of larger scale warfare seem to have been adopted including new technologies such as swords and armor. The Nara government, faced with a country of sixty-six provinces of competing clans, tried to change the Japanese military system by conscripting soldiers. By the end of the Nara period, in 792, the idea was given up as a failure.

Instead, the Heian government established a military system based on local militias composed of mounted horsemen. These professional soldiers were spread throughout the country and owed their loyalty to the emperor. They were “servants,” or samurai. An important change occurred, however, in the middle of the Heian period. Originally the samurai were servants of the Emperor; they gradually became private armies attached to local aristocracy. From the middle Heian period onwards, for almost a thousand years, the Japanese military would consist of professional soldiers in numberless private armies owing their loyalty to local aristocracy and warlords. The early samurai were not the noble or acculturated soldiers of Japanese bushido , or “way of the warrior.” Bushido was an invention of the Tokugawa period (1601-1868) when the samurai had nothing to do because of the Tokugawa enforced peace. The samurai of early and medieval Japan were drawn from the lower classes. They made their living primarily as farmers; their only function as samurai was to kill the samurai of opposing armies. They were generally illiterate and held in contempt by the aristocracy.

Buddhism developed profoundly during the Heian period as well. Situated near the capital on Mt. Hiei, the monks of the Hiei monastery developed new forms of esoteric Buddhism. The great genius of Japanese Buddhism of the time, however, was Kukai (774-835), who established in Japan a form of Buddhism called the True Words (in Japanese: Shingon) at his monastery at Mount Koya. The three mysteries of Buddhism are body, speech, and mind; each and every human being possesses each of these three faculties. Each of these faculties contain all the secrets of the universe, so that one can attain Buddhahood through any one of these three. Mysteries of the body apply to various ways of positioning the body in meditation; mysteries of the mind apply to ways of perceiving truth; mysteries of speech are the true words. In Shingon, these mysteries are passed on in the form of speech (true words) from teacher to student; none of these true words are written down or available to anyone outside this line of transmission (hence the term Esoteric Buddhism). Despite this extraordinarily rigid esotericism, the Shingon Buddhism of Mt. Hiei became a vital force in Japanese culture. Kukai believed that the True Words transcended speech, so he encouraged the cultivation of artistic skills: painting, music, and gesture. Anything that had beauty revealed the truth of the Buddha; as a result, the art of the Hiei monks made the religion profoundly popular at the Heian court and deeply influenced the development of Japanese culture that was being forged at that court. It is not unfair to say that Japanese poetic and visual art begin with the Buddhist monks of Mount Hiei and Mount Koya.

In the late Heian period, private families began to accrue vast amounts of property (shoen ) and began to support large standing armies, mainly because the Heian government began to rely more on these private armies than on their own weak forces. The result was an exponential growth in the power of the two greatest warrior clans, the Taira (or the Heike) and the Minamoto (or the Genji). The Genji controlled most of eastern Japan; the Heike had power in both eastern and western Japan.

As the powers of these two increased, the clan of the Fujiwara began to control the Emperor closely—a shrewd move since the Taika reform theoretically gave all final power to the emperor. From 856 until 1086, the Fujiwara were, for all practical purposes, the government of Japan. In 1155, however, the succession to the throne fell vacant, and the naming of Go-Shirakawa as Emperor set off a small revolution, called the Hogen Disturbance, which was quelled by the clans of the Taira and the Minamoto. This was a turning point in Japanese history, for the power to determine the affairs of the state had clearly passed to the warrior clans and their massive private armies.

After the accession of Go-Shirakawa and later his successor Nijo, a lesser lord of the Taira, a dissolute, ambitious and shrewd man named Kiyimori, began to slowly accrue massive power for himself in the Emperor’s court. Seeing this, it became apparent that the power of the Taira had to be diminished in some way, so the retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa attempted to lay a military trap for Kiyimori with the aid of a minor Genji lord, Yukitsuna. The plot failed and opened an irreparable breach between the Heike and the retired Emperor and the Genji. In 1179, the head of the Taira, Shigemori, died; his forceful and ruthless leadership had propelled the Taira into the forefront. He was replaced by his brother Munemori, a coward and poor strategist. Go-Shirakawa, seeing he now had an advantage, began to dismiss Taira in the capital, and Kiyimori fired several court officials and marched on the capital, forcing the new Emperor Takakura off the throne by installing his own one-year old grandson, Antoku, as the Emperor. Takakura enlisted the aid of the Genji and the great civil war began, ushering in the feudal age of Japan.

http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~dee/ANCJAPAN/HEIAN.HTM

Recent Comments